persephone and hades send their best from the underworld

I made a spring foccaccia recently—sliced up bell peppers as sun rays, halved cherry tomatoes into flower petals, planted artichokes in towering stalks—a story of the season told through fresh produce and processed grain. I summoned spring in a four-hundred and fifty degree gas oven and brought it with me as an offering.

The March solstice has passed over us, and the Eleusinian Mysteries made elusive promises that Demeter and Persephone would make their return to the overworld. That spring, in all of its verdant glory, would soon emerge from the winter frost. The trees in San Francisco glow a little greener in the early morning, and the warm sun has peaked out from the fog enough days to solicit endless weekends of picnicking in the dewy grass. If winter is a Faustian bargain, then spring is a contract we made with a gentler god. Spring is a promise of renewal; hope blossoms to fill the empty spaces our bodies left behind in the snow. When spring arrives, we find reason to find our faith again.

i. give me liberty, or bring me the dead

Spring comes to the overworld because Hades and Persephone struck a bargain with the rest of the pantheon: when Persphone reunites with her mother above, the world blooms; when Persephone reunites with her husband below, the world shrivels. Much has been written in scholarship about the Hades and Persephone myth (of both the academic and amateur kind). We retell the stories of seasons through these two: one of loss, betrayal, and love.

Hades and Persephone have captured the creative imagination, and this spring, I can’t help but wonder why—why a fixcation on the cyclic ending of a tragic pairing engenders a fascination with the comings and goings of a fertile season. The modern romance genre can trace its lineage back to the romanticization of Hades and Persephone. Restated in more desireable tropes, Hades is a reformed bad boy and Persephone is a good girl turned gone (perhaps even a manic pixie dream girl). It’s the contrast of dark and light that endures, and the enchanting complexity of a darkness has been wrongfully misunderstood in his good intentions and a lightness who has craved chaos and destruction to spite her golden handcuffs.

A quick online search reveals a littany of retellings borne out of the mythical Greek canon about the royal couple of the Underworld. This is a reading of Hades, as ruler of the dead (not of death; an important distinction), who deserves redemption in the softened edges of his fury. He’s a tragic and tortured figure who holds the afterlife with a cruel iron grip. He is deadly, but not death. He is dignified but not the devil; even the ancient Greek conception of the underworld was not quite the torment of Hell. There is an efficient pragmatism in the cool and collected operation of his kingdom, where he is despised and ostracized by the living when he simply finds duty in the cards he was dealt. His grip grows into an embrace when Persephone emerges, picking flowers in a green meadow. For all his misfortune and misery, Persephone is promise that Hades may be worthy of joy in his life too.

This is also a reading of Persephone, as innocent maiden turned dread queen, who had a kind soul yet vicious disposition. In the overworld, she is the graceful embodiment of fertility and vegetation; her given name, Kore, is an expression of fair maidenhood. The protective shield of her doting mother may have done her more harm than good, where her dalliance with the king of the dead is cast as a defiant streak of rebellion. This myth is also a tale of a mother’s love, but Demeter is a catalyst as much as she is the aggrieved. She is granted the credit of agency in the impossible situation of a kidnapping. Persephone was a sheltered girl who grew into a powerful woman, and when she married Hades, she lost her youthful whimsy but earned a kingdom instead. In the underworld, she is Persephone, bringer of death. She and her husband rule the lost, passed-on souls ferried across the Styx. Within the barren darkness of her adopted realm, Persephone exudes light and generosity; and in the absence of her birth realm, the fields and flowers shrivel and decay in anticipation of her return. These abandoned souls may soon feel warmth again.

ii. deathless, deathful, death struck

In a poem about Persephone, she is described as “deathless, deathful, death struck.” Lest anyone forget her namesake as bringer of death.

In one of my all-time favorite Elisabeth Hewer pieces, the first in her “the greek tragedy i’ll never write” series, Hades pleads. His hearts wants what it wants, and it wants her.

In Hadestown, the folk opera (requisite NPR Tiny Desk Concert listening) retells how Hades and Persephone fall in and out of love to the acclaim of multiple Tony’s. Spring languishes as Persephone grudgingly takes the train back to her seasonal duties, and her reunions with Hades are only a glimmer of their former sparkle. Yet she surfaces the kindness and grace in his kingship, and thus Orpheus and Eurydice are granted a second chance.

In a recent fixation of mine (and arguably, the reason I have thought enough to write this in the first place) the webcomic Lore Olympus inspires a Hellenic urban fantasy. It’s an inspired illustration of the pantheon with a modern twist, and Hades and Persephone radiate in their vibrant blue-pink hues. Hades as a king-businessman with a cool exterior hiding a complete nervous-wreck; Persephone as a young, naïve goddess marred by melancholy and wrath. The art is indulgent and lush, and for whatever it is in comic form, the fantastical digital paintstrokes make it a breathtaking read.

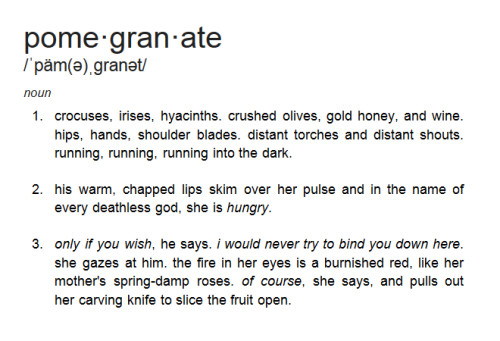

In this dictionary definition, pomegrantes grant agency.